5 Questions with Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Tiffany Tsao

Norman Erikson Pasaribu is a writer of poetry, fiction and non-fiction. He was born in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 1990.

His debut poetry collection Sergius Mencari Bacchus (translated by Tiffany Tsao as Sergius Seeks Bacchus) won first prize in the 2015 Jakarta Arts Council Poetry Manuscript Competition, and was shortlisted in the 2016 Khatulistiwa Literary Award for Poetry.

Tiffany Tsao translates Indonesian fiction and poetry into English, and also writes fiction. Born in San Diego, US, in 1983, Tsao has published five book-length translations to date.

Her translation of Norman Erikson Pasaribu’s Sergius Seeks Bacchus was awarded a PEN Translates grant and shortlisted for the 2021 NSW Premier’s Translation Prize. Her third novel, The Majesties, was longlisted for the Ned Kelly Award. She holds a Ph.D. in English from UC-Berkeley and currently lives in Australia.

(L: Norman Erikson Pasaribu; R: Tiffany Tsao)

No.1

Norman and Tiffany, you’ve had an ongoing collaborative friendship for some years now. In 2019, Norman’s first poetry collection, Sergius Seeks Bacchus (Sergius Mencari Bacchus) was translated from Bahasa Indonesia to English by Tiffany, as well as individual short stories (‘Deep Brown, Verging on Black’) in The White Review. Can you tell us how this relationship began? How has it evolved through the years?

TT: We met online! I saw the poetry that Norman had posted and thought, oh cool! At the time I was volunteering for the literary journal Asymptote and was looking for Indonesian writing to suggest to the section editors. I asked Norman if they had a translator yet, and if not, if they’d be interested in working with me to translate some samples.

NEP: What Tiff said! It’s really not a story of an author and a translator meeting in a bar. I think our relationship has so evolved that our friendship, our sisterhood, is much larger than our working relationship. I consider Tiff my family.

TT: Agree! We have weathered a lot together: optimism and disappointment, idealism and disillusionment, lows and highs. And when it comes to literary things, I feel even the highs can be low: the disparity between material reality and the apparent glamour or prestige can be so great. It helps to have a close friend and sister to process all this with.

No.2

In a profile in The Jakarta Post, Norman said, ‘A translation is an act of reassembling the body. Tiffany has given a sound to my voice. The translation process is as important as the writing itself.’ I wonder if you will share with us what this process is like. How do you both navigate this collaboration?

NEP: Usually, Tiff will come [to me] with a first draft, and I will review it. And often an Indonesian word has connotative or associative meaning that an equal dictionary English word for it doesn’t have. (For example, I feel the word ‘penjajahan’ has a more kinetic feeling than the English word ‘colonialism’.) This is one of the reasons we edit.

TT: Yes. And we’ll often edit together. Norman has the most wonderful ideas and makes the most excellent suggestions, and it would be foolish not to incorporate them. I know some translators prefer not to get input from their authors, but it feels wrong in the context of translating a queer author not to incorporate their input. It’s tantamount to silencing them even as you’re bringing their words to a wider audience.

No.3

Norman, you yourself have done translation work for others too, such as for Rari Rahmat’s poem ‘My Hair, The Diadem’ (‘Rambutku Mahkota’) in 2021. What is it like being on ‘the other side’, so to speak? I’m asking Tiffany this question too, as you have written novels in English, such as The Oddfits (2016) and The Majesties (2020).

NEP: I don’t feel like I’m on the other side, or another side. Here, everyone is bilingual, or trilingual. Yes, I don’t speak English as my first language. I often struggle with it. But I feel translation should be encouraged even when you are not a native speaker, even when you don’t really understand the thin line between “another” and “the other”. Simply because translation is an art, a fun art. And this is because translation is pretty much like mathematics—most of it is problem-solving.

TT: I think the main difference for me is that translation has more structure and writing my own work feels more daunting in the sense that I have to start from scratch. When I’m translating someone else’s work, I have a skeleton to work with—the text already exists. When I’m creating something, sometimes I’m just baffled [as to] where to start. Especially first lines: I’ll spend days and days on the opening of a chapter or a scene. There’s a part of my brain that is convinced it’s a puzzle you have to solve: there’s only one way to start and you have to figure out what that one way is or everything that follows will be awful. That decision is mostly taken away from me in translation. Well, except for the fact that I then produce several translations of an opening line and spend days trying to decide which one is the best.

No.4

Let’s chat about Happy Stories, Mostly (Cerita-cerita Bahagia, Hampir Seluruhnya): the stories are equal parts joyful, humorous, cheeky and absurdist (not to mention the wordplay!). To me it is tragicomedy at its best; often I found myself simultaneously cackling and sighing in recognition as that is often the case for many people on the margins, particularly in societies that don’t embrace or celebrate queerness. Happiness is often so close, yet ultimately out of reach.

Norman, you’ve said in the author’s note that ‘Hetero readers hate sad-all-the-time fictional gays, but often put in zero effort to make us, who are gay in flesh, happy. It’s a sad irony. […] But let’s be real: can you, as a queer, be happy in the way the heteros are happy in Indonesia? Happiness requires an endless list of privileges, in any part of the world. It is often the heteros that block us from accessing happiness.’ Can you speak more to this? How do your stories form, and what do you see as some leading themes when you embark on the writing process? How different do you view this as compared to when you write poetry?

NEP: Stories often came to me as voices, as in a mental picture of someone saying anything: the way they mouth their words, how their lips move, the colour of their teeth, the colour of their voice, whether their voice sounds angry, or upset, or sad, or excitedly happy. There are secret histories in the way people talk when you speak to them, and in these you will find stories. An example of this is [the short story] ‘Metaxu’—it started when a picture of a woman, ‘a sister’, appeared in my head. She was fixing the camera with which she recorded her confession to a priest, opening it with, ‘This is a story…’

I don’t think separately for my fiction or poetry. When I was writing the stories in this book in Indonesian, most of the time I was thinking, I am writing longer poems. As I am writing this answer, I am not in the mood to talk about Indonesia. Last week, the minister of law here tweeted about the urgency to criminalise LGBTQ+, just so Indonesia has legal clarity about it. About us: real, breathing humans. And he tweeted that in the most “oh bro my bro” way to one of the parliament leaders. [So] can you actually talk about ‘happiness’, so called ‘damai sejahtera’, when some people think they have a veto power regarding your very existence?

No.5

Tiffany, you have translated other books from Bahasa Indonesia to English in the past, such as Laksmi Pamuntjak’s The Birdwoman’s Palate (Aruna dan Lidahnya) and most recently Budi Darma’s People From Bloomington (Orang-orang Bloomington), amongst others. Norman’s careful, lyrical style is obviously informed by the fact that he is a poet; I wonder if you will tell us if there were any challenges and/or surprises that occurred for you during this particular translation process?

Not for Happy Stories, Mostly. Perhaps this was the surprise: that the translation process flowed so easily in comparison to their poetry collection Sergius Seeks Bacchus. But I think Norman and I spent a lot of time laying this foundation during the translation of Sergius: we chatted so much, corresponded so much, reworked countless versions, listened to each other reading the poems to get a better feel for the rhythm and music of the poems. I feel Happy Stories, Mostly and Sergius Seeks Bacchus are not disparate translation projects, but two stages of the same ongoing partnership I have with Norman–the ongoing project to translate their work.

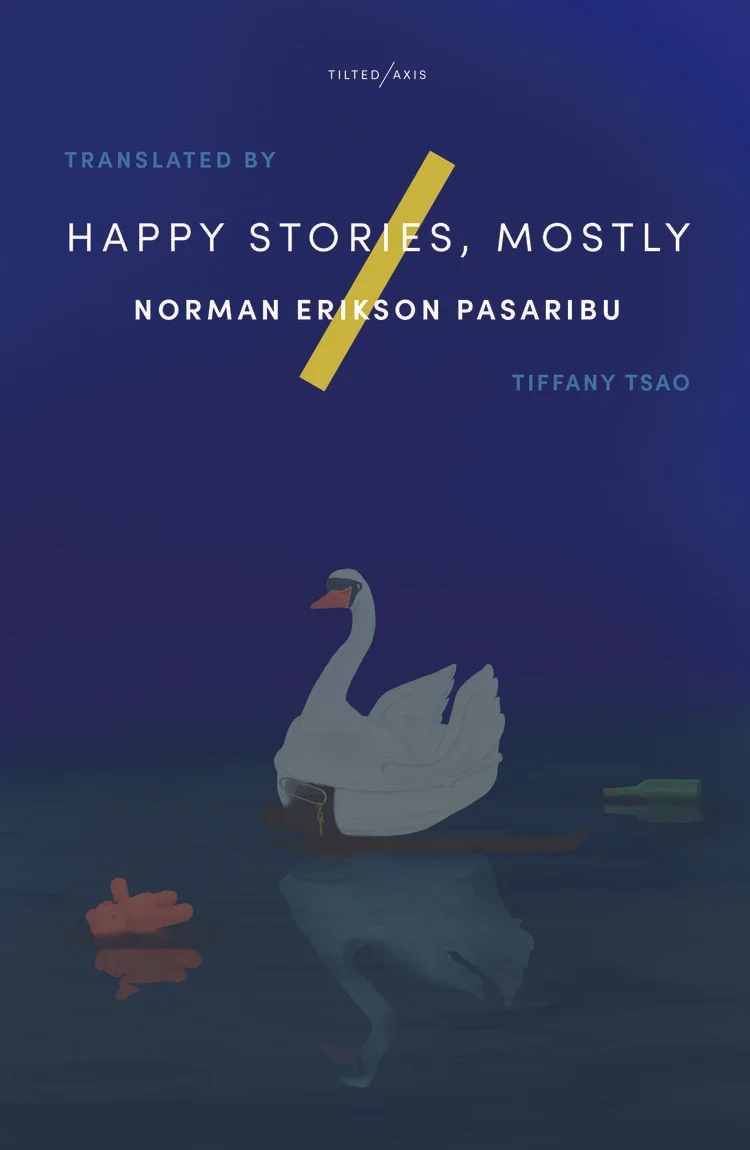

Top: AUS edition (Giramondo); Bottom: UK edition (Tilted Axis Press)

Watch and hear Norman and Tiffany read from Happy Stories, Mostly Below:

Winner of the Republic of Consciousness Prize For Small Presses 2022.

Longlisted for the The 2022 International Booker Prize.

Powerful blend of science fiction, absurdism and alternative-historical realism that aims to destabilise the heteronormative world and expose its underlying rot. Translated by Tiffany Tsao.

Inspired by Simone Weil’s concept of ‘decreation’ and drawing on Batak and Christian cultural elements, in Happy Stories, Mostly Pasaribu puts queer characters in situations and plots conventionally filled by hetero characters.

In one story, a staff member is introduced to their new workplace - a department of Heaven devoted to archiving unanswered prayers. In another, a woman’s attempt to vacation in Vietnam after her gay son commits suicide turns into a nightmarish failed escape. And in a speculative-historical third, a young man finds himself haunted by the tale of a giant living in colonial-era Sumatra.

Get it from Giramondo Publishing here or at all good bookstores.