5 Questions with Kaya Ortiz

Kaya Ortiz is a queer Filipino poet of in/articulate identities and record-keeper of ancient histories. Kaya hails from the southern islands of Mindanao and lutruwita/Tasmania and is obsessed with the fluidity of borders, memory and time.

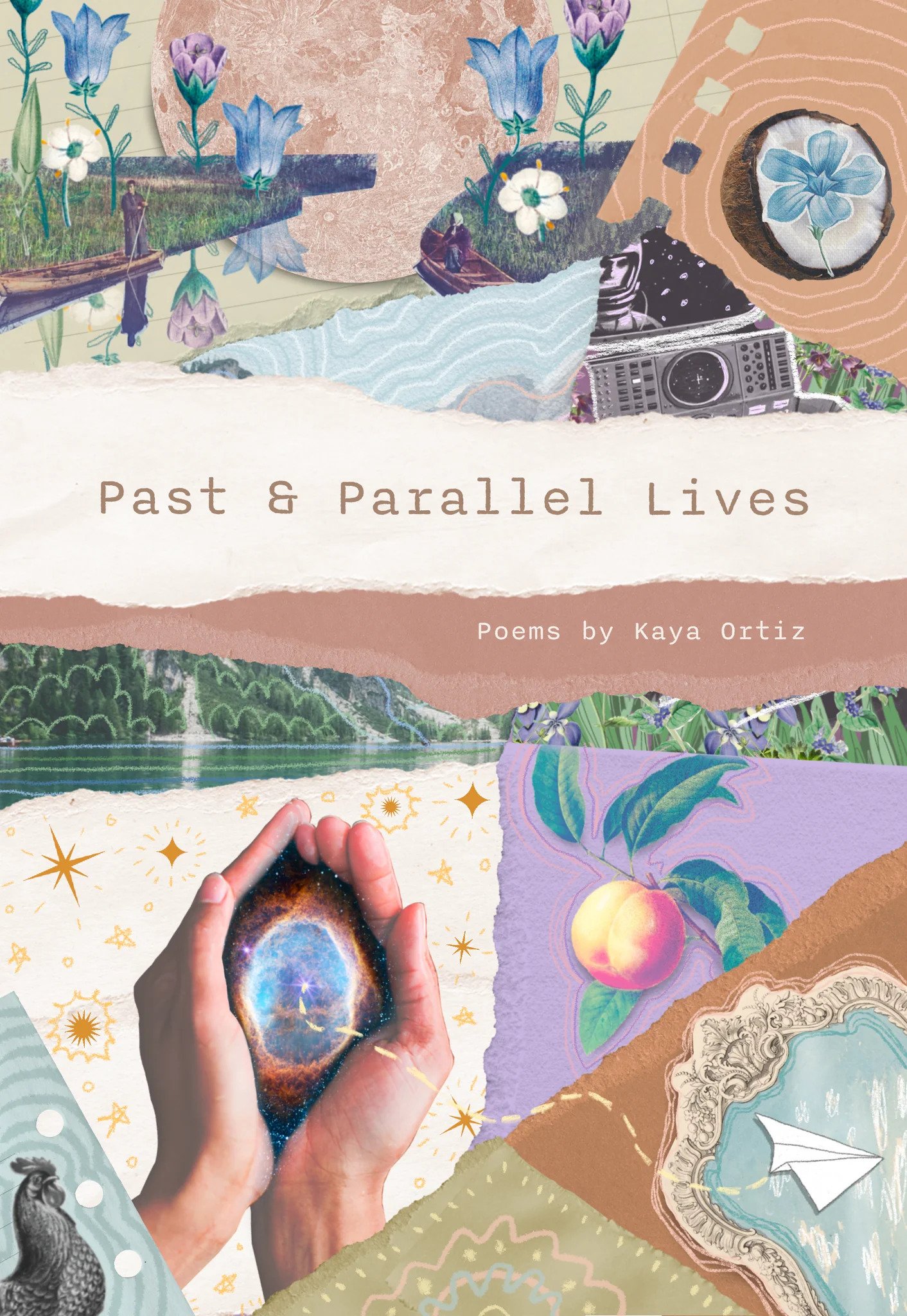

Their writing has appeared in Portside Review, Westerly, Australian Poetry Journal, Best of Australian Poems 2021 and After Australia (Affirm Press 2020), among others. Winner of the 2024 Dorothy Hewett Award, their poetry collection Past & Parallel Lives is out with UWAP.

Kaya lives and writes on unceded Whadjuk Noongar country, where their name means ‘hello’ in the Noongar language.

No.1

Past & Parallel Lives is your first poetry collection, on being alien, queer and other. How did the collection come about, and what was the process behind ordering the poems in three sections (‘requiem’, ‘reincarnation’, ‘revelation’)?

Past & Parallel Lives is the culmination of a body of work I’ve been building since I first started on the poetry scene around eight years ago. Most of the poems are not that old, but my obsessions with certain themes and stories (being alien, queer, and other) do go back that far. Sometimes it felt like I was just writing the same poem, or the same three poems, a hundred different times. So it made sense to build the collection around them.

I always knew it would be in three sections (three is a good number). I also wanted it to have a vague narrative structure [where there was a] beginning, middle and end. In my first draft I organised the poems into themes of loss, longing and self-acceptance, and those sections were later re-named. That makes it sounds so simple, but there was definitely a lot of shuffling around as a lot of poems fit thematically into more than one section. I partly resolved this by cutting up a few poems and having a part in each section—essentially giving the poems parallel lives, or what I call ‘suites’ (for example, the ‘Ritual’ suite or the ‘Easter’ suite). This was before the final title for the collection came about so looking back, it was kind of an inspired and inspiring decision!

No.2

A surprise awaits between the pages of Past & Parallel Lives: there’s a zine within, also titled Past & Parallel Lives. Can you speak more to that? What was the decision behind including that inside the book?

I like making art about my obsessions. It helps me channel the many feelings I often have about them. In this case, the obsession was my own work. That sounds very egotistical. What I mean is, this was a project I’d been thinking about and working on for over two years, and it was hard to transition out of that rich creative space post-book. So I made five mini zines about the book as a way to transition and channel those lingering thoughts and feelings. I also made them as a way to tell people—via art and vibes—what the book is about, because I find it difficult to sum it up in a way that does it justice.

I tend to communicate best through art and poetry. And zines are very tactile artifacts. I see the process of collaging and zine-making as similar to poetry, so a zine to me is like a poem you can hold. Unfortunately the zines are not included in every copy of the book, just the ones reviewers received, although I wish we could’ve done that! I do give zines away to people in person, and I gave them away at my book launch too. I like the idea of having a nice little memento.

No.3

Why poetry as a form and not something else?

This is a very poet thing to say, but it’s true: I didn’t choose poetry, poetry chose me (I think Philip Larkin said it first).

It’s hard to articulate the feeling poetry gives me. I’ve written stories since I was a kid, which my parents encouraged. Terrible angsty poems as a teenager, of course. Attempted a fantasy novel then too. But poetry found me again at 21 through spoken word videos on YouTube, particularly Safia Elhillo’s Alien Suite, which I will mention every time because it changed my life. I was studying English at uni; I already loved language and literary theory and telling stories. But poetry showed me that there are infinite possibilities for recreating language, that it can cross boundaries and hold multitudes. Poetry demanded I see myself and the world in a different way. It showed me that my life could mean something other than a pre-assigned blueprint; that I could break all the rules and make something entirely new.

I know other forms of writing and art can do these things too. For me poetry was the medium I needed—fluid and nebulous enough to hold all of me, while also offering structure and form and craft to build upon.

No.4

What keeps you centred and open to new possibilities for language, considering your poetry also typically involves Tagalog and Bisaya words and phrases? How do you stay in the fluid space where you can always see new possibilities?

I think part of it is living in translation. English is the language I’m most fluent in and it’s what I primarily speak now, but Tagalog and Bisaya words and phrases sometimes try and find their way out when I least expect it. Often when that happens, I can’t express myself exactly how I’d like to because no one would understand me. At the same time I think having that distance from Tagalog and Bisaya allows me to hear and understand it in new ways, to parse out meaning or make connections I might not see otherwise. I like thinking about literal meanings and transliteration and interpretation.

The other part is, I think it’s just how my brain works. In my day-to-day life, I like using precise language to convey meaning; I like accuracy and clarity and I don’t like being misunderstood. That usually means being slow and intentional when I speak, and always thinking deeply about words and patterns and the possibilities for meaning.

All of this translates into poetry and how I engage with language. Part of the beauty of poetry, for me, is that I can let go of the desire to be understood. I can let go of accuracy and clarity in favour of a more nebulous, emotional truth in a playful space that is rife with possibility.

No.5

In a longform interview with you (also in Liminal, #162 in 2021), you talk about not using conventional poetic forms often, so you create your own structures to work with. You said you enjoy “experimenting with form and the visual aspect of the poem”, as well as “the challenge of fitting a poem into a structure”. It seems Past & Parallel Lives is crafted largely in this way. Can you speak more to this?

Form is play, poetry is play, writing is play. There’s so much joy in creating something from the ground up. Conventional poetic forms like sonnets, sestinas and villanelles offer structure and scaffolding that can result in really beautiful, powerful poems.

Those forms aren’t something I use all the time because I don’t want to force a poem into a shape that doesn’t suit. I use them when I feel that the poem demands it; that’s something I have to listen for when I’m writing a poem. I think form is the part of poetry that is most like visual art. It’s the first thing you notice, how the words look on the page. I love how form allows the words to shine, and can also shed light on a poem’s context, or give added meaning to the work. Like the contrapuntal form I used for the poem ‘Habi (Woven)’, which features in the interview you mentioned, and is partly about time and how past, present and future intertwine through memory. The form in that poem is itself something woven, with alternating lines moving in and out of each other like a braid.

Then there’s poems like ‘Self-insert Trek: Flashback’ (published in Cordite 110: POP!), which does not follow a prescribed structure. [When I was writing it], it compelled me to use all sides of the page, to incorporate blank spaces, to have different line lengths in order to tell this story which is simultaneously concealing and revealing, which is scattered and unsure and afraid. Spending time listening to the poem (which really is just listening to a very quiet voice inside myself) and building the form and structure the poem needs, it feels like accessing a powerful part of the human experience, which is the act of creation and the act of attention, something I have to try ever harder to hold onto these days.

Find out more

Time. Memory. Mirror. Past & Parallel Lives is a rippling reflection on being alien, queer, and other. These poems yearn for home and belonging after migration, religion, and coming out. Kaya Ortiz’s award-winning debut shines with authenticity – this is a courageous departure from a past life, towards a queer future and a poetic return to self.

Get it from UWAP here.