5 Questions with Monica Macansantos

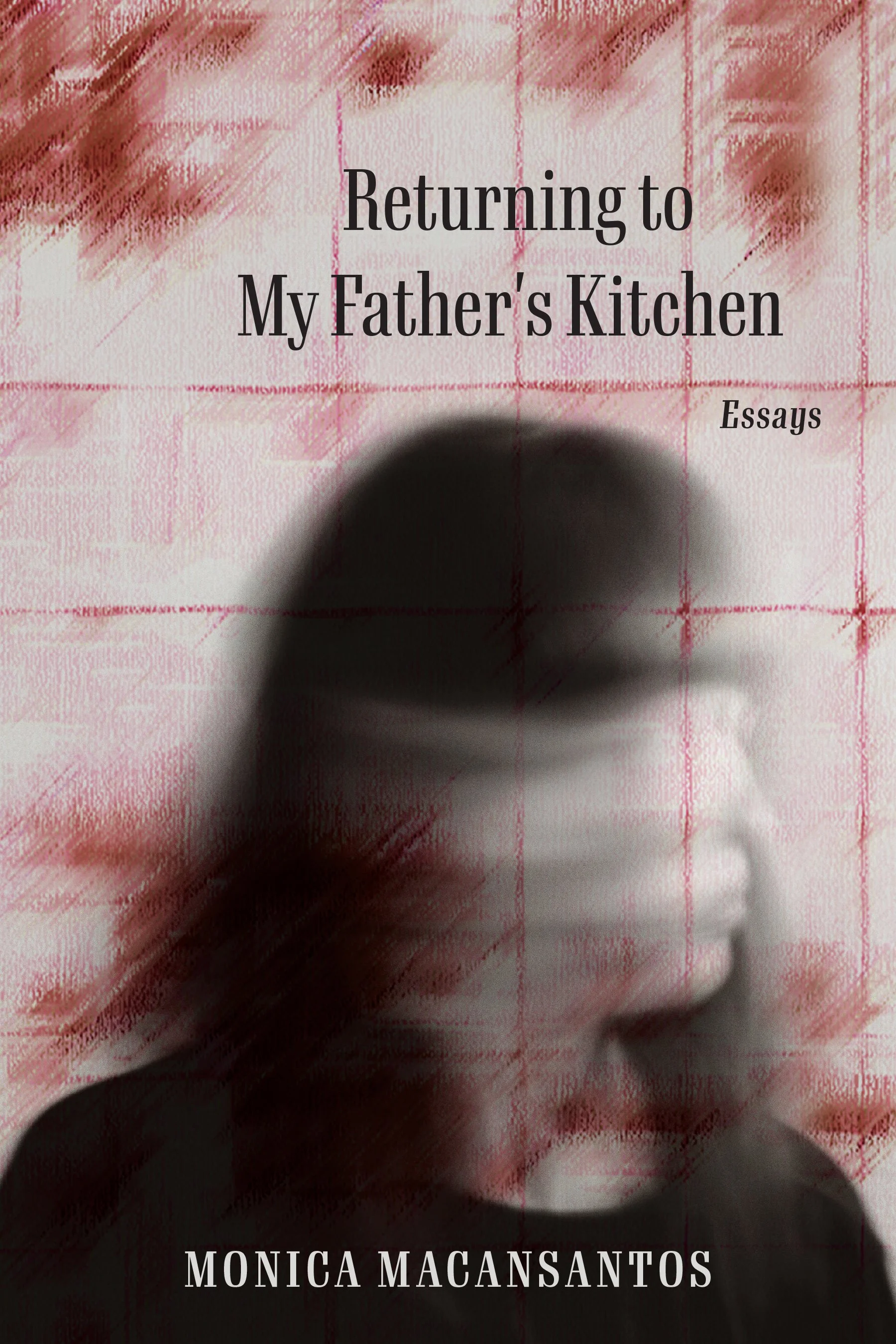

Monica Macansantos is the author of Returning to My Father’s Kitchen: Essays (Curbstone Books/Northwestern University Press, 2025), and Love and Other Rituals: Selected Stories (Grattan Street Press, 2022).

She was a 2024-2025 Shearing Fellow with the Black Mountain Institute at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and is a 2025 Marguerite and Lamar Smith Fellow with the Carson McCullers Center in Columbus, Georgia.

Her work has recently appeared in River Styx, Bennington Review, Electric Lit, and Lit Hub, among others. She earned her MFA as a James A. Michener Fellow from the University of Texas at Austin, and her PhD from the Victoria University of Wellington, International Institute of Modern Letters.

No.1

Your first book, Love & Other Rituals, was a story collection. You return now with an essay collection, which comes after you return to the Philippines from living abroad after your father’s death. How were the essays in Returning to My Father’s Kitchen collected, and when did you realise that you were circling around similar topics for this book to materialise?

Though I had written some personal essays when my father was still alive, it was after his very sudden and unexpected passing that I began to turn to the nonfiction form in earnest. The few personal essays I had already written helped me confront my complicated feelings about my homeland, the Philippines, while also examining my connections with other places I’ve called home, such as Newark, Delaware, where I had spent my formative years while my mother pursued her PhD on a Fulbright Fellowship. Nonfiction had always afforded me the means to ground myself in memory and place, and I turned to the genre to regain my footing in the world after my father’s passing. It’s a feeling that many people who have experienced life-changing loss are familiar with—the feeling that the ground on which we stand no longer gives us the stability we crave, now that the people in our lives whom we once depended on for safety and comfort have been snatched away from us. I basically felt lost at the time and needed a roadmap for finding my way through the world in my father’s absence. For this, I needed to turn inwards and reckon with the places and characters that had shaped me. Nonfiction was the perfect vehicle for this, and it inevitably took me back to the memories my father and I shared, our family history, and the places we called home.

I had the feeling that I was working towards a book while writing these essays, but it was during the pandemic, which effectively marooned me in my hometown of Baguio, that I was forced to see these essays as parts of a larger project. Quarantine forced us all to reflect on the themes I mull over in the book, such as mortality, loss, and our rootedness in the places we call home. It was during the pandemic that I wrote the remaining forty percent of the book, and these were essays that served as connective tissue for the collection. Essays like ‘A Shared Stillness’ which is about learning to tango in New Zealand and connecting with my family history in the process; ‘My Father and W.B. Yeats’, which is about contemplating my father’s journey as a spiritual seeker by re-evaluating his poetry; and ‘Katherine Mansfield’s Light’ which contains my own meditations on mortality while diving into Mansfield’s short oeuvre, were all products of pandemic isolation and how this let me turn further inwards.

No.2

Of course, the throughline between both collections is of Filipinos in the diaspora. What do you think the role of fiction and nonfiction is, and how did you approach the research and writing process for each book?

I’m not sure how satisfying my answer will be to this question, because I generally agree with Teju Cole who says that there really is no difference between fiction and nonfiction, and that western narrative conventions have forced us to make hard distinctions between the two. Not because I don’t believe that ‘there’s no such thing as objective truth’ (because I believe there’s actually such a thing), but because I feel that both fiction and nonfiction are vehicles for truth, with differences in their approach.

What I noticed when I turned to nonfiction (as someone who was trained academically as a fiction writer) was that the form made me turn inwards and examine my own motivations more deeply, even when I was writing about circumstances that involved other people and entire societies. Every essay was a means for me to venture more deeply into myself, and to confront parts of myself and my history that I hesitated to look at for extended periods. This was the case even when I was writing about Filipino or New Zealand culture, and I turned to nonfiction to figure out my place in these cultures and societies.

When I write fiction, on the other hand, I’m motivated by the need to understand other people—usually friends, or ex-friends, or people I’ve crossed paths with, or people I’ve read about in news articles. I’ll witness an incident involving these people, or else I’ll overhear an anecdote, and I’ll feel intrigued enough to explore their stories imaginatively through fiction. I’m usually motivated by the need to understand other people’s motivations, and I’ve been particularly intrigued by the immigrant experience, and how the pursuit of success in foreign lands leads some to behave in morally questionable ways. Like, why would a father abandon his children in pursuit of Australian citizenship, and what is it about the immigrant success story that gives people license to behave in ways that hurt themselves or the people they love the most? And how does this cycle of hurt perpetuate itself in the next generation? This isn’t the only question I think about when I write fiction, since I also write about Filipinos in the homeland who have no intentions of leaving the country, but one theme that ties my stories about Filipinos at home and in the diaspora together is our failure, at times, to behave ethically and with kindness (and our valiant struggle nonetheless to do so, given the circumstances).

As a writer, I’m glad to have dipped my toes in both forms—both have enabled me to gain a deeper understanding of the human experience by making me turn outward through fiction, and inward through nonfiction.

No.3

How do you know when a project is finished?

Do we ever know? In my case, I feel like a work of literature can be released into the world when its limbs are fully developed, and it can stand on its own without my assistance. That isn’t to say, however, that the project is ‘finished’ in the truest sense of the term. I imagine my published stories and essays having their own lives in the world, and their own encounters with discerning and generous readers that enable them to grow and take on new meanings. This is the beauty of art—it’s a living, breathing, growing thing. Who knows if I’ll take down one of my essays or stories from the shelf years from now for another rewrite.

No.4

What is something creative you haven’t done but would like to do?

It would be interesting to learn how to compose music—my father was an amateur songwriter, and I think that music composition can teach us how to bring disparate parts of a project together to produce a full and satisfying piece with sections that speak meaningfully to each other. However, I’m not sure if I have the talent for music composition—I played the piano in grade school and made up songs when I was much younger, but I certainly can’t compete with professional composers.

No.5

What other essay collections were you inspired by while writing Returning to My Father’s Kitchen?

I remember reading Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror while writing my own essays and liking it a lot—our essay collections are very different, but I was inspired by her use of the essay form as a means to explore a question and its ramifications in her personal life. In many ways, my essay collection does that too, though I tend to begin with a memory before the question arises from it. In that way, my essays are probably more similar to Rebecca Solnit’s—though I’m embarrassed to admit that I only started getting into her work after completing my essay collection.

I absolutely loved Roger Reeves’s Dark Days: Fugitive Essays, which I guess is worth mentioning even if I read it after I completed my own collection. I started out as a poet, and Dark Days showed me how the essay form could serve as my way back into poetry (while also enabling me to seek answers to difficult questions). Dean Young’s The Art of Recklessness served a similar purpose when I was an MFA student at the Michener Center—Young was Reeves’s mentor, while Reeves was my classmate in Tomaz Salamun’s poetry workshop.

When I was a very young writer in the Philippines, I found a second-hand copy of E.B. White’s The Second Tree From the Corner and fell in love with his prose and the way he found magic in the most ordinary of moments. I grew up with E.B. White’s children’s novels (I’m still moved to tears when thinking about Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little) and it was a pleasant surprise to find that my favourite children’s author wrote essays that spoke to me as an adult.

My father was a Paul Theroux fan, and we had his travel essay collections in our house. I know he gets a bad rap (and rightfully so) for his colonialist tendencies, but I read his essays as a teenager and was inspired to get out of my small town in the Philippines and see the world, thanks to his work. Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, on the other hand, inspired me to return to my sleepy hometown in my essays, and to seriously think about the ways in which its landscapes have shaped my psyche.

Find Out More

Feeling untethered after her beloved poet father passes away while she is living abroad, Monica Macansantos decides to return to the Philippines to regain her bearings. But with her father gone and her adult life rooted in the United States and New Zealand, can the land of her birth still serve as a place of healing?

In fifteen richly felt essays, Macansantos considers her family’s history in the Philippines, her own experiences as an exile, and the parent who was the heart of her family’s kitchen, whether standing at the stove to prepare dinner or sitting at the table to scribble in his notebook. Macansantos finds herself remaking her father’s chicken adobo, but also closely rereading his poems. As she reckons with his identity as an artist, she also comes into her own as a writer, and she invites us to consider whether it is possible to carry our homes with us wherever we go.

Get it from Northwestern University Press here.