5 Questions with Natalia Wikana

Natalia Wikana is a writer, book reviewer and freelance beta/sensitivity reader.

While dealing with her terrifying stacks of unread books and writing her own, she champions diverse stories.

No.1

How did your essay ‘Catching Meaning’ come about?

When Black Inc. Books announced a call for submissions for Growing Up Disabled in Australia, I was working on a fantasy novel. It features a protagonist who shares my disability because disabled people do kick ass and have adventures, and there was little representation on intellectual disability. I was also tired of disabled people being seen as ‘inspirational’ yet portrayed incorrectly by non-disabled creators and actors. Society is never seen as being the source of our struggles and hate.

[Being able to write for] Growing Up Disabled in Australia gave me the chance to directly address that without fictional counterparts. It opened up a lot of wounds: vivid memories of growing up that I hadn’t talked about, shared or thought about too much when working on my fantasy stories. I decided to take the opportunity to write about them and release my long buried hurt and frustration. But as I wrote on, I noticed how far I’ve come and decided to structure my piece around my growth.

No.2

What first drew you to writing?

I’ve always felt drawn to creating stories, in particular characters, since I was a kid. It was an escape and provided solace as it was one of the few things I was good at. While I struggled with learning and communicating, I had a busy, imaginative mind. I’m not sure what truly inspired my interest in creating stories, but films did have a major role—I used to re-enact scenes and play out dramatic scenarios with my toys. I also wrote fanfic character profiles relating to existing stories, even inserting my own original characters, because I couldn’t get enough of those worlds and was fascinated with the idea of giving life to and projecting one’s own experiences, desires and fantasies onto people who aren’t real.

But I didn’t take writing seriously until I picked up Twilight (I’m not ashamed of that!) when I was around 18. The rush of an intense romance and situation, and a protagonist who reminded me of myself inspired me to write my first novel. It opened up a never-ending hunger in me to build and devour worlds. That’s when I knew that becoming an author was my calling. It felt right.

No.3

As a novelist, what is an integral part of your creative practice?

Definitely a morning of procrastination (haha) to warm myself up before getting down to business. That time includes happy scrolling through social media news feeds, completing my five-minute daily Mandarin session, going down the internet rabbit hole and discovering random facts or watching an Asian drama and Buzzfeed Unsolved.

On a serious note however, plotting out my stories and jotting down key scenes/moments before writing and fleshing out my characters, figuring them out, then later revising them are important parts of my process. It’s also important to me that the characters’ identities and cultures are a part of them, even in fantasy—I do justice to that by doing my research.

No.4

When I read ‘Catching Meaning’, I gathered that there were multiple intersections of ‘not fitting in’ whether it was at school, amongst other Asians and later in the publishing industry. How did you end up finding community?

Until I got to my early twenties, it seemed like I was cursed to not fit in. I struggled to connect due to my disability and anxiety, yet was too ‘attached’ to people who didn’t want to be friends or moved on quickly.

So I feel lucky to have found some good and supportive friends through the book community, and a place in that community as well as the writing one on Twitter. It started with just me talking about books and throwing my thoughts into the void. Social media was where I learned about BIPOC and disabled readers who were going through similar experiences as me. I was hesitant to interact with them at first, but that was fleeting as I began to feel safe in their virtual presence—and of course we had books to talk about!

Not only was I accepted, but over time, I also grew to embrace myself and the differences that shape me as I became more aware of topics concerning identity and culture, which have helped me get to know other writers of marginalised backgrounds, leading to partnerships and friendships offline.

No.5

In an ableist world that prioritises ideas of ‘productivity’ over rest and slow contemplation, how do you think you balance (or: reject) this? What advice would you give to a young, disabled writer who is struggling with this?

I’m still a work-in-progress when it comes to dealing with this. But I can tell you so far that being organised, asking around [for advice or help], and taking notes are key. It helps with avoiding overload, and thus anxiety.

Currently, being a freelancer has accommodated my needs, especially in terms of having the time to take things in, such as instructions, discussions and messages. That said, being a freelancer also invites too much flexibility and that can be disruptive even if there are deadlines, so I write up a schedule for each day/week, blocking in a couple hours of work throughout the day and fit in as much short breaks to physically and mentally breathe as I need in between.

A little writing, even just a sentence, or none at all is still productive, as you can come up with the most epic idea or piece of writing from taking a rest and reset. Being a writer has also taught me that I don’t have to rush into submitting things until my work feels right, until I’ve read everything very carefully and done my research. It’s also okay to let people know you need time to think and get something done, and ask for help if needed.

And one last thing, don’t worry about not submitting your work and not participating in a contest or project if you’re not ready. There will still be opportunities coming your way when you are.

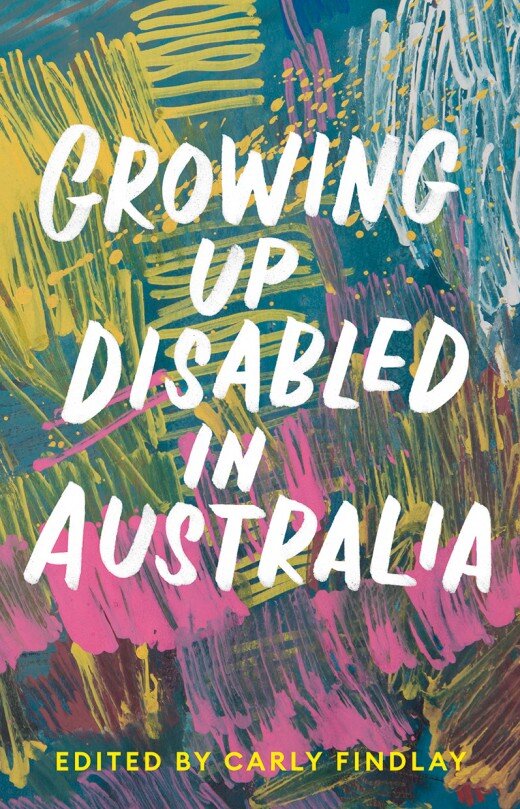

Growing Up Disabled in Australia is a rich collection of writing from those negotiating disability in their lives—a group whose voices are not heard often enough

One in five Australians has a disability. And disability presents itself in many ways. Yet disabled people are still underrepresented in the media and in literature. In Growing Up Disabled in Australia—compiled by writer and appearance activist Carly Findlay OAM—more than forty writers with a disability or chronic illness share their stories, in their own words. The result is illuminating.

Read an extract here.

Get a copy from all good bookstores now. An audiobook version is available on Wavesound.