5 Questions with Vijay Khurana

Vijay Khurana is a writer and translator.

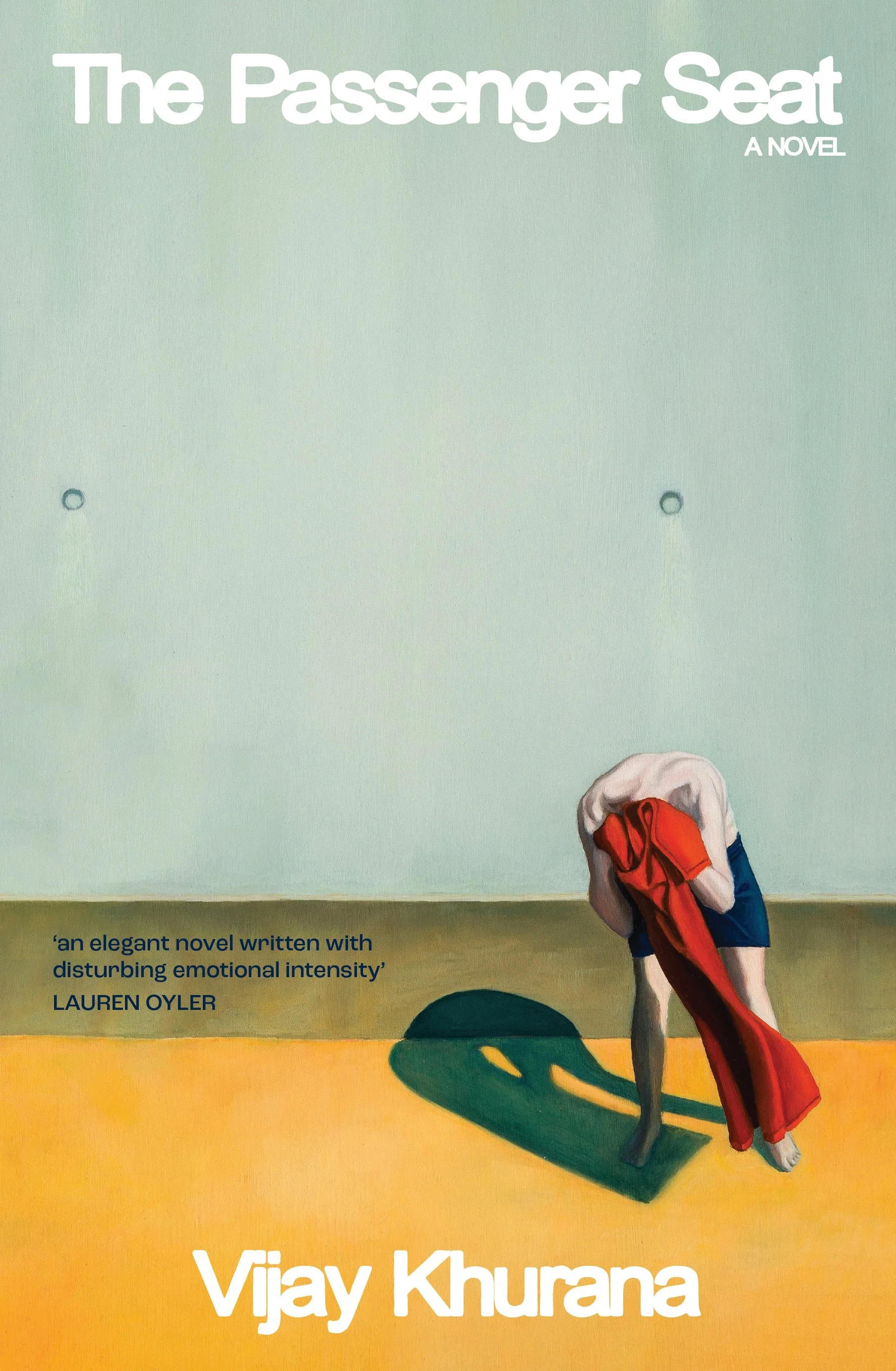

His debut novel, The Passenger Seat, was shortlisted for the 2022 Fitzcarraldo Editions/New Directions/Giramondo Novel Prize, while his short fiction has been recognised by numerous prizes and published in The Guardian, 3:AM Magazine and NOON, among others. He has also been a presenter on Australian radio station triple j, and in 2014 he published a children’s chapter book, Regal Beagle.

No.1

What do you remember as your earliest literary sensibilities and interests, and how did it evolve to become what it is now?

I learned German at school and went on to study it at university, so my introduction to literature involved being captivated by German-language short stories. I remember Kafka’s “The Judgement” and Wolfgang Borchert’s “The Rats Sleep at Night” especially. When I was fifteen, I spent around six months living in Germany, and the idea of being able to read in another language was very exciting to me. I’m sure that reading German and translating from it have affected how I write in English.

Earlier on in my life there was something else, a fascination or obsession with voice. I don’t mean voice in a literary sense, I mean the actual human voice—whether it was scanning a radio dial, my mother reading to me before bed, the cassette letters my English grandmother would record and send to us in Australia, or the books I had on tape, like The Wind in the Willows and The Railway Cat. There was always some undefined connection between reading and listening. I’m still interested in voice and voices. I read all my work aloud as I redraft because the way it sounds is important to me, but voice isn’t just about style. It can also be a mode, a novel’s way of thinking, like in Beckett’s The Unnameable.

No.2

Your debut novel The Passenger Seat is a tense story that revolves around Teddy and Adam, two young men in small-town Canada. How did the seed for this narrative evolve while you were writing?

In around 2018, I was living in the UK and I noticed that I had been writing quite a few short stories about masculinity and friendships between young men, and over time I sensed it was something I wanted to explore more deeply. I also read about a real-life event which ended up informing parts of the novel, as well as thinking back to the road trips I had taken as a young man with (mostly) male friends around southeastern Australia.

I wanted to pick through the road trip trope and to explore its paradoxes, like how it’s about both the limitless freedom of the open road and the confinement of the vehicle, and how the vehicle is a bubble that makes for a highly-mediated experience of ‘seeing the world’. I tried not to assume a certain shape or destination for the novel but let the writing itself decide what it wanted to be, at least in the early drafts. The title came relatively early on, and with it came questions about passivity, dominance and power dynamics within male friendships. The question of which character is ‘in the driver’s seat’ and which is ‘in the passenger seat’ becomes increasingly unstable as the story goes on.

No.3

In recent times there’s a lot of talk regarding ‘toxic masculinity’ as we see the rise of alt-right white male figures like Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate, et al. Studies are showing that young men are becoming more right-wing in their views as well, which points to something of a contemporary ‘crisis in masculinity’, even though the idea of the violent man is as old as time itself. Can you speak to this in relation to The Passenger Seat?

I know very little about the specific names you mention, but I was interested in the way men often create or adopt narratives that may seem comforting but end up being harmful to themselves and people around them—especially when those narratives encourage them to think of themselves as tragic heroes and victims of injustice. It can happen in the context of ideology, and Adam in The Passenger Seat consumes things of that sort, including a book that is somewhere between self-help and a guide to manipulating people. But I think it goes beyond media and ideology.

The second part of the novel focuses on a character, Ron, who was only briefly mentioned in the first part. He has a tangential relationship to Teddy and Adam, and tells himself that he is a victim of their actions in a very specific way. But as the book draws to a close, we’re invited to question that narrative. I think there’s a similarity between Ron’s kind of narrativisation and the political narratives that Adam is buying into.

The question of there being a crisis in masculinity is also interesting to me. It’s so hard to argue against that being the case, but at the same time, ‘crisis in masculinity’ is inevitably a kind of short-hand, a simple label for a complex, intersectional and often ambiguous issue, and that’s something I was writing against with this novel. I think we need to keep hold of the complexity and the ambiguity, which is why I think fiction is a useful place to go to explore issues like this.

No.4

In a review of The Passenger Seat, critic Catriona Menzies-Pike notes that you’re ‘a writer who has matured outside the networks and institutions that sustain most Australian debuts’. I agree with this: there’s a remarkable overturning of the usual tropes that permeate Australian realist novels. Perhaps the fact that you’re a translator helps as well. Do you have much of an opinion about the Australian arts and literary landscape, considering you had worked as a Triple J presenter for some years and published a children’s book before you moved away?

I have written stories set in Australia, but I’ve never felt that Australia was something I needed to write through or towards, despite its being my home and despite all the ways it has shaped me. My parents were immigrants who had each brought a culture with them, and I also spent some of my childhood in the UK, which may explain why my writing as a whole isn’t strongly tied to a particular place.

Around 2010, when I last lived in Sydney, my sense of the arts landscape was shaped quite heavily by my involvement in the music scene through Triple J. I self-published a few stories as zines, and wrote magazine columns, but I wasn’t part of anything so cherished as a writing community. I remember having some glancing interactions with writers at places like the This is Not Art festival in Newcastle and a Sydney reading series called Penguin Plays Rough—there was a strong DIY energy that I hope is still coursing about.

Several writers I’ve come across lately seem formally very exciting. I’m thinking of people like Michael Winkler, Sanya Rushdi and Jen Craig. And I’ll be back in Australia to take part in some book festivals later in 2025, so I’m looking forward to going to bookshops and catching up on what I’ve been missing.

No.5

What was the most important thing you learned while embarking on your MFA, that ended up in how you thought about or structured this book?

That the internal tensions of a sentence—its sounds, its rhythm, its shape—are just as important to a story and its meaning as things like character or plot.

(Credit: Alexander Coggin)

Find Out More

Approaching the wrong person with open hands can be fatal.

Seeking escape from their small-town existence, two teenagers impulsively drive north, with no particular place to go and no particular sense of who is at the wheel.

Adam and Teddy hope to leave boyhood behind, but as the journey progresses their friendship becomes a struggle to prove themselves. When Adam harasses a young couple they meet on the highway it lands them in trouble they cannot run from.

In taut and stylish prose, The Passenger Seat examines how men learn and perform masculinity. Rejecting easy answers, it keeps our eyes trained on the vanishing point where vulnerability edges into violence, alienation into aggression.

Get it from Ultimo Press here.