Copies Can Lead

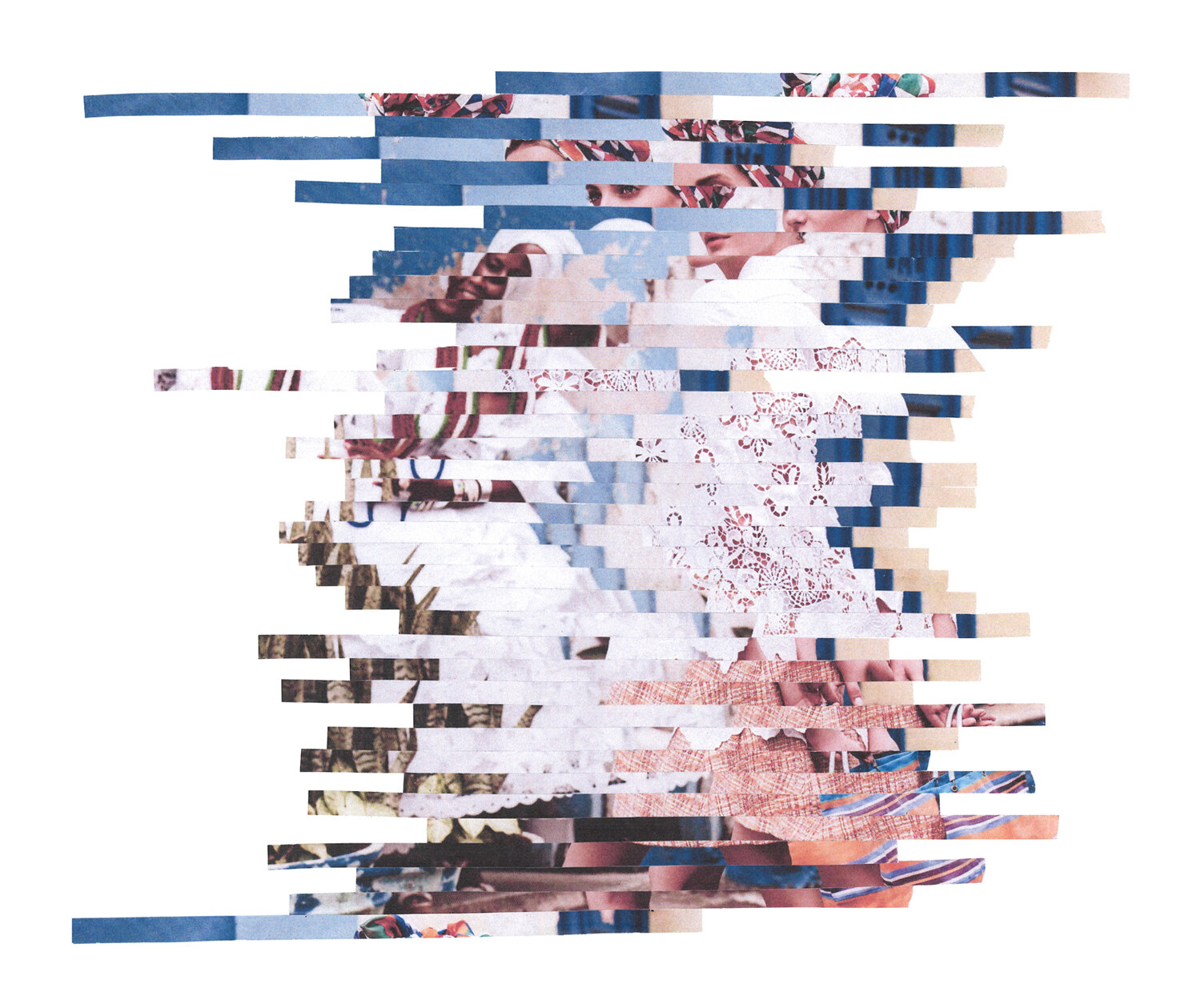

Roberta Joy Rich, Arrest No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3 (Arrest Triptych), 2020

(Image description: A colour photograph is repeated side-by-side in triptych. The far-left photograph shows a White woman wearing white cotton embroidery, skirt and a headwrap, looking ahead with a bag tucked behind her back. In the background is a Black woman, slightly out of focus, wearing a white embroidery dress, beaded necklaces and headwrap. The centre image has more cuts and slides, with the White woman skewed to the side, her mouth filled with black colour. Horizontal strips of colour (green, pink, clear turquoise waters, sunsets and a daisy field) have been added to the centre image to create a distortion effect. The far-right image is sliced horizontally, with each slice sliding both left and right, scrambling the image to no longer look like the original image.)

words, sculptures

sculptures, terms

clothing, trademarks

classify, histories

repeating you

and me and us

copies can lead to transformation

(so) walk forward, arm up, clench fist, head tilts up

Copies can be described in any way imaginable. Short and sharp copies; long and detailed copies. The imitation of a sensual neck-kiss once seen in a brilliant film. Answers scribbled from a best friends’ exam paper. The world’s weight seems to rest on the idea of a ‘copy’; everything we have is indebted to it—books, theories, visuals, melodies. Without copies, all might be lost.

It’s the year 1665, and the tower of Nanjing in Eastern China is sitting tall and pretty. A multi-tiered tower, flanked by lanterns, built with splendid white bricks of porcelain. It’s so pretty in fact that Dutch explorer Johan Nieuhof is doing what Dutch explorers do: he publishes a drawing-copy of the tower to an enraptured home audience, in particular the Dutch Queen Mary II. To better orient the queen’s exotic curiosities, a copy of the tower is made: a Flower Pyramid vase designed for the Queen’s tulips. It is a recent Turkish import.

The Tulip Pyramid is having a viral moment, and soon the Dutch are duplicating it en masse using a custom ’delftware’ material. These copies are widely celebrated, but for a single crucial element: the original Tower of Nanjing’s ornate porcelain. As such, Dutch clients request Chinese potters to create similar pyramids to European design and specification; to produce a copy of a Dutch copy, of a drawn-copy, of the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing. Come the 1800s, the Dutch have gained an ability to produce porcelain themselves, and as such this trail of copies goes cold…

It isn’t until 2016 that Jing He revives this lineage to confront a question of identity and a soft-crisis of design. Two questions are posed in Tulip Pyramid – Copy and Identity: what does it mean to have a Chinese identity, and what is Chinese design? Born in the southern Chinese city of Kunming in 1984 and later on going to study at the Dutch Design Academy of Eindhoven, Jing reflects on this straddling of worlds: “I sympathise with the Chinese who share my profession. I understand their anxiety in the search for a Chinese identity in European discourse, especially since Chinese identity seems to be defined by European discourse.”

In this search for identity, Chinese modernity is the site of an ongoing anxiety: “Contemporary Chinese generally feel that they are living in a temporary stage of history. Our lives are always preparing us for future, not the present.” As economic development occurs throughout China, intellectual property laws move at a slower pace. With China’s recent and oft-cited history of counterfeits in mind, Jing reflects on the Eurocentric perception that “[Chinese people] are good at copying but not at critical thinking and that they cannot think outside of the box.” As a response, her work pivots away from the pretension of authenticity to be found in ‘originality’; instead, Jing ventures to “learn from the phenomenon of copying in China instead of denying it.” The Tower of Nanjing and its numerous copies will become the foundation of something made anew.

*

It’s the year 2016, and my wander around the wonderful Kinokuniya bookstore leads me to a copy of Jing He’s Tulip Pyramid - Copy and Identity, an introduction to her art practice. Four years later at the art studio Testing Grounds, I find myself repeating behaviours day after day for months, trying to understand what it means to be a resident artist, to have an art practice for myself. Amidst all of my own copying, the work of fellow resident Roberta Joy Rich becomes known to me.

It’s the second half of the 20th century, and the term ‘Coloured’ is diffuse throughout Southern Africa: a racial classification hoisted on a scaffolding of bureaucracy and policy. The term is borne of an immense white supremacist, anti-Black operation of Apartheid. Apartheid means ‘apartness’ in Afrikaans, a creole language made up of the First Nations Khoi and San people’s dialects, Portuguese, Indonesian, Arabic and variants of Malay (though often singularly attributed to the Dutch and their colonial presence.)

‘Coloured’ replicates through official policies, resistances, social practices, cultures, movements. Language adapts and shifts with use, and consequently so do the impacts of a classification. In the life of a word, meaning can be recalibrated, titles renamed and reclaimed. Renaming and reclaiming is foundational to Roberta Joy Rich’s art practice, and it’s where I meet her. I find her rejigging officiated government documents, magazine clippings, buildings, geolocations and acts of solidarity to reckon with histories of classification and notions of alleged authenticity. Born in Geelong in 1988, her work flourishes between Naarm (Melbourne), Johannesburg and Cape Town, places that weave through her own African diasporic identity and experiences. Her public work has a sleekness and accessibility to it. This conceals a labyrinth of concepts and references that are a surface-scratch away, a labyrinth that contains academia, histories, officiated government documents and languages. ‘Coloured’ winds its way through this tangle; its numerous copies will become the foundation of something made anew.

*

words, sculptures

sculptures, terms

clothing, trademarks

classify, histories

repeating you

and me and us

copies can lead to transformation

(so) walk forward, arm up, clench fist, head tilts up

Amid its constant replications, copies have an inevitable relationship with mistakes. The imitation of a vase design gone askew. A crucial piece of jewellery missing from an otherwise effortless cosplay. A cover of a pop song with misheard lyrics. Sometimes these mistakes are just that. But the discomfort arising from a mistake can conceal the opportunity to create something new.

These moments of friction within a canon of copying have huge consequences—these frictions are also known as glitches. While the term is a spillover from the technological world, glitches also live in the world of flesh. A train signal displays the wrong destination, placing commuters on the wrong journey. Someone realises they’ve gained access to a place, somewhere they aren’t meant to be in. Though it’s often thought that glitches only occur through aberration—free from the world of ethics because they’ve happened by accident—a glitch can be manufactured and guided. Here, something new can be made from a pre-existing process: a copy wherein imperfect replication is fully intended.

Both artists have taken a scalpel to histories and cultures, engineering their very own glitches. Jing answers the question of a Chinese design identity by embracing its history of copying. This leads to two new Tulip Pyramids: a rogue interpretation of the myriad copies that came before. The first Pyramid is the result of multiple artist collaborations, where different designers are invited to design each layer of the pyramid. Plastics, porcelain, LCD screens and wireless routers constitute this intriguing and disjointed structure. The second Pyramid reifies the worlds that Jing straddles: its very design is inspired by five renowned Dutch designers. Non-digital materials including cloths and plastics make this structure—atop the pyramid stands a 3D print-out of Jing He’s head, the word ‘fragile’ imprinted on it.

Meanwhile, Roberta has lifted the term ‘Coloured’ and placed it onto clothing: front and centre on a jumper, the letters filled with colours reminiscent of South Africa’s description as a ‘rainbow nation’. ‘Coloured’ is embellished with a trademark, bringing the term into the world of copyright and intellectual property.

Jing’s new Tulip Pyramids embody a similar notion. Though Queen Mary II’s tulip vases are listed under a public domain dedication, new copyrights sprout from these new pyramids. “I would like to make the ownership and authorship of this pyramid ambiguous, to discuss more IP issues in collective authorship and copying,” she notes. A glitch has been born from these balances of ’playful creation and serious research’. “Copying can have transformative potential,” Jing continues.

Place the ‘Coloured’ jumper on. Feel a literal fabric of history rubbing skin, producing warmth as it was never intended. What responsibilities do you have when you wear this copy, which conversations do you enter? Come to know these pyramids, as they celebrate a history of copying oft-derided and imbued with a colonial disdain.

Glitches can act like circuit breakers, slips in the crack that can be taken advantage of. Stepping through time can reveal how glitches work in our favour. It can show hundreds of years worth of Chinese ingenuity, or a lineage of brown South African citizens whose genealogy connects to African First Nations Khoi and San peoples. It can affirm Kurdish voices, freedom fighters aimed at by the state, whose honour might be maintained through writing. Searching cultural plains, digital architectures and canons of design we can take copies, produce copies, make something anew. Sourcing, copying, ripping, pasting, removing, replacing: engineer a glitch.

Ava Amedi is a writer, musician and artist. He works across songwriting, artist interview, performance, poetry and non-fiction. Key to his work is a desire to deliver affective experiences to audiences.

His recent work has been made with the support of Arts House, The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, un Projects and Djed Press. You can find him @alumied on social media.

Roberta Joy Rich's work responds to constructions of 'race' and gender identity, sometimes with satire and humour in her video, performance, installation and multi-disciplinary projects. Drawing from historical, socio-political, media and popular culture, Rich engages with notions of ‘authenticity’ and its relationship to constructed identities and their forms of representation. In doing so, Rich aims to de-construct colonial modalities through arts practice while ascertaining empowering forms of self determination, often referencing her own [diaspora] African identity and experiences.