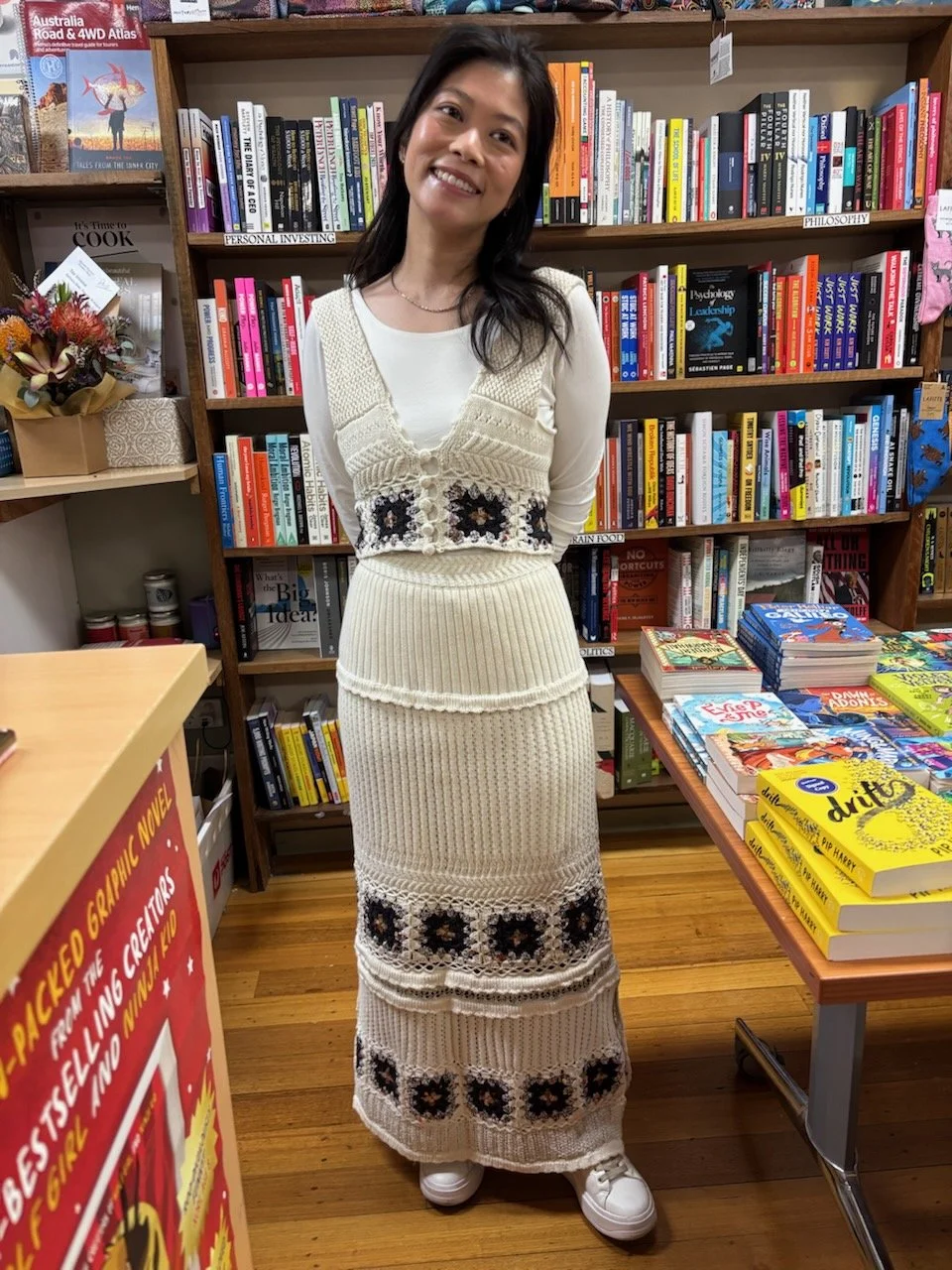

5 Questions with Belle Ling

Belle Ling was born and grew up in Hong Kong and has lived in Australia. She is a co-winner of the Peter Porter Poetry Prize, a Fellowship Awardee by the Playa Residency in Oregon, and a Lucy Morris Stevens Scholar awarded by the Emmanuel College at the University of Queensland.

Her first poetry collection A Seed and a Plant was shortlisted for The HKU International Poetry Prize; her poetry manuscript Rabbit-Light was highly commended in the Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize (2018); her other poetry manuscript Grass Flower Head was shortlisted for the First Book Poetry Prize of Puncher and Wattmann and a semi-finalist for The Brittingham & Felix Pollak Prizes in Poetry.

Her works could be found in World Literature Today, Chicago Quarterly Review, the Australian Book Review, the Atlanta Review, Cordite Poetry Review, Mascara Literary Review, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, and others. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Queensland.

No.1

What kinds of things, from your experiences living in Hong Kong and Australia since you were a child, made you interested in creative writing? Why poetry specifically?

I remember language has always held a special place for my life since I was young. My mother told me that when I was around the age of two, I responded to her with a verbal variation of an almost parallel couplet. She said, “It’s raining, you’ll have no chance to go out with me.” I immediately replied, “It rains heavily, you pop up an umbrella, carrying me on your back to go out with me.”

There was another instance too: I was obsessed with thesauruses, especially English ones. During my secondary school years, I relished reciting words that are almost synonymic but not quite: linguist, language specialist, linguistics scholar, polyglot, grammarian.

And speaking of creative writing, I first fell in love with Chinese literature, amazed by the subtle emotions and layers of complexity hidden in imagery. I remember, as a child, I liked reciting the San Zi Jing (Three Character Classic) and various classical Chinese poems from the pre-Qin, Tang, and Song dynasties. I just enjoyed, and still do now, how poems can speak so much within such a small, condensed space.

No.2

Over the years, you have had a few poetry manuscripts shortlisted for prizes, as well as individual poems having won awards. How did Nebulous Vertigo evolve from these?

To be honest, Nebulous Vertigo evolved from a very different tree branch of my writing—from when I was studying for my PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Queensland. My very first shortlisted manuscript was called A Seed and a Plant, largely about my upbringing and childhood in Hong Kong. I guess it garnered my attention towards something that felt very pure and not yet destroyed in my heart, which is what Nebulous Vertigo tries to reclaim. The other shortlisted manuscripts, Rabbit-Light and Grass Flower Head, are the forebears of Nebulous Vertigo. They both articulated a very imagistic ambience, [containing] the ghostly residuals of those who have passed away. From these manuscripts, I tried to play with the possibilities of incorporating my understanding of Cantonese expressions, Chinese writing practices, and my Hong Kong-related upbringing into English poetics.

During my PhD, I wanted to evade cultural silhouettes. I always thought, especially back then, that I needed to “write like a western poet”—this kind of thinking, I admit, is a colonial relic. As I am led to reflect more deeply upon my poetics, with the encouragement of my supervisor, I gradually understand that I can never cut myself off from my origin if I want to find my own voice. That is how the shortlisted and award-winning poems came forth—“63 Temple Street, Mong Kok”, “One Intimate Morning”, and “Cucumber and the Catbus Club”, They speak with a dark humour tinted with childlike innocence and curiosity, which is a very signature voice of Hong Kong—or at least, of “my” Hong Kong.

No.3

Nebulous Vertigo can be said to be multi-vocal, in the sense that it explores the versatility of the English language when intertwined with the Hong Kong Chinese context you grew up in. Can you speak more to this?

I am very glad that multivocality can be spotted in NV. It is easier for me to talk about this using one of my favourite poems from the book, “So, Is That How Light Travels?”. It’s not exactly my “favourite” but rather a poem that still intrigues me after it was finished. The poem springs from an erroneous Chinese character—”nightmare”/嘔—that I wrote in one of my secondary school composition pieces. But I wrote the wrong Chinese character, which means “disgusting”/惡; whereas the correct one is a character with four mouths (that is how “crocodile”/鱷) is rendered in Chinese as well) which refers to “dissonance” and “fear.” But these two characters—the wrong one and the standardised one—are pronounced the same. It makes me very curious about what is happening between them: Why can’t a nightmare be rendered “disgusting”? Why is it wrong? What’s the difference between “disgusting” and “fearful” when it comes to an unwelcoming experience in the realm of dreams? How many kilometres are there if a person has to travel from a feeling of disgust to fright? Who gets to draw the boundary within such a subjective experience?

And then, I started to think about how in my schooling, I was often corrected, often taught to follow rules, often commanded not to cry in front of others, and punished for not listening to teachers and parents. Meanwhile, interestingly, the prevailing ambience of my upbringing was interrupted by the inspiration from Zhuangzi, a Taoist philosopher who champions “free wandering” and “the unintentional flow of existence”. Like Zhuangzi, I want to use parables to frame my linguistic struggles and my childhood dilemma of choosing between my own voice and the expectations of authority.

The English language inhabits a very fitful aesthetics for this. I do not need to explain anything like a sinologist. In English, “nightmare” is a “nightmare”—or, you could say, a very bad dream. And yes, for sure, it can be a frightening, disgusting, uneasy dream. This is how linguistic fluidity comes into the picture. I inserted my own narrative of writing the two Chinese characters—one meaning “disgusting” and the other “fearful”—to explore the unspoken subjectivities related to “nightmare” in my upbringing. In this case, I am not explaining the literal or linguistic difference between these two characters. I am trying to flow with the undulations of cultural waters as I shuttle between the uncharted parameters of Chinese and English.

No.4

What are some of your favourite poetry collections?

I have a lot. My recent favourite is Jenny Xie’s Eye Level. It opens my eyes to how the sentiments hidden in Chinese culture could be experienced when they are so beautifully and surprisingly rendered in the English language. Eye Level has its succinct indirectness and in- depth simplicity.

Others would be Rainer Maria Rilke’s Book of Hours, Adam Zagajewski’s Without End, and Louise Glück’s Faithful and Virtuous Night. They all carry a sharp eye for the pain and helplessness of humanity with a mysteriously flimsy voice, which delivers a very precious sacredness. My all-time favourites are, without a doubt, the poetry of Wallace Stevens, Pablo Neruda, and Matsuo Bashō.

No.5

What advice would you give to a fellow bilingual aspiring poet?

Be truthful to your own voice. Trust in the origin from which you come. Open your eyes and ears to the minute subtleties and any interesting fabric and mosaics that you encounter every day. Don’t be afraid to articulate things in a “weird” way—you can always discover something that is yet to be discovered between languages. Remember that language is a very fluid thing, and you can always be the agent and creator, so long as you give yourself and language a chance.

Find Out More

Formally daring poems that ask a compelling question: if fate can never be changed, how can we embrace its weaving?

The realm that belongs to Nebulous Vertigo is both visceral and vibrant, and it is mysteriously familiar. If you come close to it, you will hear how rains eat, how a silken tofu revolts, how the Chinese word for “beans” turns into a speaking persona, and how a telephone bridges the surviving and the afterlife. In Nebulous Vertigo, everyday life is inevitably lost to the inevitable fate. And yet, with unexpected quivers, our fate and life keep surprising us.

Traveling through the cha chaan teng in Hong Kong, you can hear how Mrs. Suen, Mr. Yuen, and Waiter Kuen carry out intriguing conversations; astounded by the night sky in Paris, you will see how constellations narrate the lovers’ quirky destiny; and all the way through the Sayama Hills in Tokorozawa, you will be surprised by the turnings and upturnings of the myths told by a Japanese Uncle. Nebulous Vertigo, as its title beckons, “sighs an unreal cloud / for the fated sun to rise.” If fate can never be changed, how can we embrace its weaving? Every attempt, as the poems suggest, can be calmingly adventurous, unobvious yet magnanimous.

Get it from Tupelo Press here.